Measles is making a resurgence in the United States, with dozens of children in multiple states contracting the highly contagious viral disease so far this year. Measles has become a bigger problem in the United States and globally recently for many reasons, but there is widespread speculation that COVID-19 is not to blame for its resurgence.

as early AprilAccording to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 113 measles cases have been detected in 18 states, with Illinois reporting the most. Two-thirds of the cases involved children, with half involving children under 5 years old. No deaths have been reported, but 65 people, including 37 children under the age of 5, have been hospitalized due to complications from isolation or infection.

Measles was partially eliminated in the United States in 2000, meaning that cases of measles now seen in the country often come from elsewhere. But outbreaks can and do sometimes spread here. Some of the seven ongoing outbreaks in the United States date back to late last year, but the total number of cases is already double the number of deaths reported in 2023 and is on track to be the most cases since 2019, which saw more than 1,200 cases. example.

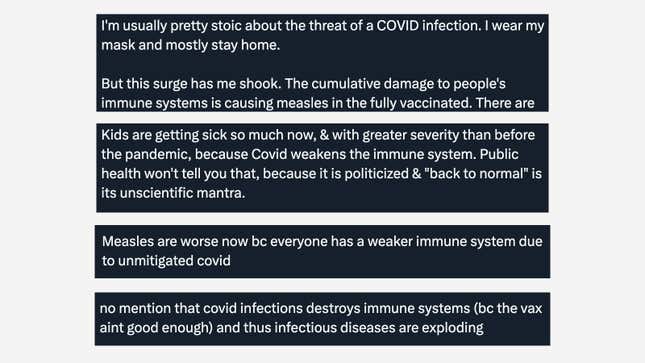

If you scroll through social media posts discussing these outbreaks, you’ll quickly see people pointing to covid-19 as the culprit. Some believe that since the coronavirus is known to weaken people’s immune systems, it must provide fertile ground for measles to re-emerge. It’s not just measles—similar arguments have been made to explain recent increases in tuberculosis or unusual outbreaks of disease, such as the 2022 cluster of severe pediatric hepatitis cases in several countries. Some have even gone so far as to nickname “covid”airborne AIDS” – It is known that untreated HIV infection can lead to other opportunistic infections.

The big problem with this hypothesis is that, at least for measles, there’s really no need to propose a special explanation for its return. The measles virus can spread very well between people who have never been exposed to the measles virus before. So as long as enough people in a community are not immune to measles, there’s always a chance that measles will cause a wildfire of disease if given the opportunity. Measles remains endemic in many parts of the world, so there is no shortage of new sources of outbreaks.

“Long before covid-19 emerged, the unvaccinated population was There have been measles outbreaks among the population.”

All states mandate that children be vaccinated against measles and other once-common germs before entering the public school system.While national childhood measles vaccination rates remain high (93.1% in the 2022-2023 school year), they have recently fallen below the 95% threshold that experts say is needed to ensure limited spread within the community (a concept known as herd immunity). Vaccination rates are even lower in some areas of the United States, giving measles greater room to spread if it emerges in these areas.

From an immunity perspective, there is nothing surprising about these recent outbreaks. According to the CDC, 83% of cases involved people who were unvaccinated or whose vaccination status was unknown, while another 12% involved people who had received only one of the two doses of the vaccine required for measles. Measles vaccination is very effective and long-lasting (more than 99% protection is achieved with two shots), but it is not completely foolproof, so it may occasionally happen in vaccinated people, especially if the virus is allowed to spread over a period of time. If spread within the scope. The community is long enough.

Another obstacle is that there isn’t much evidence to support the idea that the coronavirus is broadly weakening our defenses against other germs.

“There is no evidence that COVID-19 or the vaccines adversely affect people’s immune systems,” Richard Rupp, a pediatrician and director of clinical research at the University of Texas Medical Branch’s Seeley Institute for Vaccine Science, told Gizmodo. “Measles has always been a concern. I think people’s image of measles is red spots on the face, or someone sitting there like a sad sack. But no, it’s always been a serious disease.”

Known life-threatening acute COVID-19 cases wreak havoc impact on the immune system, they can be improved A person is at risk of contracting other bacterial infections at the same time, although this is true with any serious infection. Some people also experience persistent symptoms (including mild symptoms) after being initially infected with COVID-19, a condition called long-term COVID-19 infection. There is evidence that at least some cases of long-term infection may be related to persistent harmful changes in the immune system triggered by the infection.

But even these changes seem to be just examples Immune dysregulation and overactivation, rather than the kind of long-term immune deficiency that might make a person more susceptible to other infections (which does happen with HIV). At a population level, there is no data to suggest that rates of known opportunistic infections would explode as you might expect if COVID-19 weakened everyone’s immune systems. Like the recent measles epidemic, coronavirus is rarely needed to explain every mysterious cluster of illnesses that emerges. For example, a strange wave of serious childhood hepatitis cases in 2022?Now it seems that it is caused by a previously unknown interactions The relationship between a common virus and a rare genetic vulnerability to severe infection by it.

Frankly, there is no good reason to consider COVID-19 “airborne AIDS.” Treating it this way does everyone a disservice. Covid remains a real public health problem (at least 48,000 Americans died last year, according to CDC provisional data), and those with long-term Covid deserve more attention and research. But blaming every other health problem on the coronavirus is both inaccurate and distracting.

For example, the epidemic did have a real impact on the global resurgence of measles because it disrupted or diverted resources Existing measles vaccination programs, Especially in poorer countries. Disinformation about covid-19 vaccines spread by anti-vaccination movements may also have undermined public confidence in other vaccines. So defeating measles requires reminding people around the world of the value of vaccination and ensuring they have easy access to it.